Implementation Evaluation And Maintenance Of The Mis Pdf

The RE-AIM (reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance) framework, which provides a practical means of evaluating health interventions, has primarily been used in studies focused on changing individual behaviors. Given the importance of the built environment in promoting health, using RE-AIM to evaluate environmental approaches is logical. We discussed the benefits and challenges of applying RE-AIM to evaluate built environment strategies and recommended modest adaptations to the model. We then applied the revised model to 2 prototypical built environment strategies aimed at promoting healthful eating and active living. We offered recommendations for using RE-AIM to plan and implement strategies that maximize reach and sustainability, and provided summary measures that public health professionals, communities, and researchers can use in evaluating built environment interventions. ROLE OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT IN PUBLIC HEALTHThe increased understanding among behavioral scientists, public health practitioners, and planning experts of the built environment's role in promoting healthy behavior and reducing health risks (e.g., pollution, inactivity, accidents) offers an opportunity to use a transdisciplinary approach to addressing major risk factors associated with many of the leading causes of death (e.g., cancer, respiratory and heart diseases, unintentional injuries).

- Evaluation And Maintenance Of Mis Ppt

- Implementation Evaluation And Maintenance Of The Mis Pdf Format

Furthermore, because emphasizing the physical location where individuals encounter an intervention will influence which populations are reached, how often they are reached, and whether the environmental change has a positive, neutral, or negative effect (e.g., does transit-oriented development increase a community's access to desirable retail services or lead to gentrification and displacement of low-income residents? RE-AIM DimensionDefinitionQuestions and ChallengesBuilt Environment–Specific Metrics aReachNo.

ACan also be used to assess change over time in each dimension.For example, reach (absolute number, percentage, and representativeness of those affected by the environmental change) is challenging to calculate when considering potential and actual users of public space. To paraphrase a line from the movie Field of Dreams (Universal Pictures, 1989), “If you build it, will they come?” is the reach question relevant for built environment interventions. For example, if a neighborhood makes environmental improvements such as sidewalk and bike lane additions and traffic calming initiatives (e.g., stop signs, curb extenders) to increase active (i.e., pedestrian and bike) transportation, who is being reached?

Identifying the target population that could potentially use the sidewalks and bike lanes—in this case, residents of the neighborhood where improvements were made—and then capturing who actually uses them requires collecting data on the target population and then conducting observational or survey research before and after installation.In instances in which geographic boundaries for the designated target population are not clearly defined, researchers will often use buffer zones, or circular areas, around the specific geographic location approximating the catchment area for expected users. The size of the buffer zone may vary according to the ubiquity of the destination (e.g., coffee shop vs specialty food store), its importance to a community's daily life, and the location of the intended users (target population). Thus, a coffee shop's buffer zone may be a few blocks, and a specialty food store's buffer zone may be the entire city.Continuing with the active transportation example, assessing effectiveness may require measuring whether there are different effects across different subgroups (e.g., did the installation of bike lanes, sidewalks, and destinations increase active transportation or reduce the number of car trips among those who will most benefit, and were there any unintended negative outcomes, including social justice issues?). USING RE-AIM TO DESIGN AND PLAN SUSTAINABLE ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGESOne advantage of built environment interventions is that they can influence the behavior of large and diverse segments of the population.

In addition, once built, such projects are likely to be sustained, although maintenance will be required to retain their intended use. Because construction costs for built environment changes can be high, careful planning that includes the intended users as well as those who will need to approve, construct, and maintain the environmental change is essential.Each dimension of the RE-AIM framework can be used as a blueprint for planning. We recommend planning for evaluations of the intervention from the start, including identifying metrics readily available from public sources (e.g., crime and accident statistics), and identifying means by which behaviors can be tracked routinely and efficiently (e.g., store and restaurant register receipts, electronic benefit transfer machines at farmers' markets that allow use of food stamps, and routine customer surveys). Training community groups in the use of qualitative methods, such as systematic observation and walkability audit tools, may encourage the involvement of the community in maintaining the environmental change. Finally, identifying milestones up front and establishing ways to frequently report progress and celebrate the achievement of milestones are important for projects that may require months or even years to complete.

RE-AIM DimensionPlanning StageFarmers' MarketComplete StreetsReachIdentify target population whose health or health behavior could benefit.NumeratorPostimplementation observation of no. Of shoppers at various times and days and assessment of their demographics (age, gender, race).Postimplementation observation of no. To demonstrate how the revised RE-AIM framework can be applied to built environment interventions, we described 2 exemplars based on composites of actual community strategies employed in Colorado during the past 3 years (see ). These exemplars are also summarized in.

The example strategies have been endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as ways to combat obesity and are representative of built environment strategies now being implemented by communities across the country. The first strategy, “farmers' market,” addresses barriers related to fruit and vegetable access and consumption. The second strategy, “complete streets,” encourages active transport. Farmers' MarketA coalition was formed to address obesity issues in a low-income community.

Plans were drafted for an evening farmers' market that would be situated in a centrally located church parking lot to address the lack of a grocery store within the predominantly Latino neighborhood. The coalition defined the denominator for calculating reach as the estimated number of households within 1 mile (1.6 km) of the proposed market site, given that households beyond 1 mile tended to be composed of non-Latino Caucasians, a group that was not the primary focus of the market. Plans to track customers included observing the number of visitors to the market (i.e., to estimate the numerator for reach) and using vendor sales information to determine the volume of fruit and vegetable purchases.To ensure that the farmers' market would be approved and would appeal to the target population, the following partners were included in the planning process: the neighborhood association, the police department, the parent–teacher organization, local family farmers and ranchers, the church priest, and a nearby Latino social organization. The implementation was assessed in both quantitative and qualitative terms. Quantitative data included number of vendors per week and variety of fruits and vegetables offered.

Qualitative data included information gathered from a focus group of community members formed to help provide an understanding of food needs, pricing, and the optimal location for the market. Maintenance plans were not discussed, although a potential future need to relocate the market was raised as a result of concerns about liability from the church and complaints about increased traffic from some of the neighbors. Complete StreetsThis strategy applied smart growth principles related to land use planning and transit-oriented development to revitalize a city's central retail district and encourage commerce in a historic low-income area. Plans called for the surrounding street network to be retrofitted according to complete streets guidelines, which promote roadway designs that increase safety and accessibility for users (e.g., bicyclists, pedestrians, transit users, and motorists) of all ages and abilities. Complete streets designs typically include sidewalks wide enough to accommodate wheelchair users, bike lanes, and traffic calming elements (e.g., reduced speed limits).

Because public transportation improvements associated with the revitalized space served residents within 3 miles, the target population was defined by the city as those living within a 3-mile buffer. A desired behavioral outcome was an increase in active transportation behaviors among individuals commuting to the revitalized district.Bicyclist, pedestrian, and transportation data were assessed through periodic observations and intercept surveys conducted within the district. Adopters included in the planning, approval, and design of the project were government officials (city manager, public works personnel, and traffic engineering personnel), representatives of businesses (chamber of commerce, grocery stores, and restaurants), and resident groups (bicycle organizations, seniors groups, and neighborhood associations). The coalition charged with implementing the project assessed fidelity to smart growth principles by evaluating the city's master plan and recommending ways to adapt it to meet land use guidelines. Maintenance plans included ongoing tracking of perceived barriers and business satisfaction and profitability; this information was collected through town hall meetings hosted by the coalition and the city council. The ultimate goal was to add language to the city's master plan to ensure application of smart growth and complete streets principles to all future land use projects. RE-AIM DimensionFarmers' MarketComplete StreetsReachNumeratorObserved average no.

Of daily shoppers (100)Observed average no. Of daily visitors (2000)DenominatorResidents within a 1-mi buffer of the market (1000)Residents within a 3-mi buffer of the district (7000)Score a0.10 (100/1000)0.28 (2000/7000)EffectivenessDescriptionAverage no. Of customers per day who purchase fruits and vegetables (60)Average no. Of visitors per day who walk, bike, or take public transportation to commute to the retail district (100)Score a0.60 (60/100)0.05 (100/2000)Adoption (inclusion/approval)NumeratorNo.

Of agencies and organizations accepting the invitation and participating (9)No. Of agencies and organizations accepting the invitation and participating (20)DenominatorTotal no. Of agencies and organizations invited to participate in establishing the farmers' market (10)Total no. Data communication and networking forouzan 5th edition chapter 2 ppt. CScore is a subjective rating ranging from 0.0 (unlikely) to 1.0 (very likely), of the likelihood that built environment changes (and resulting reach and effectiveness) will be sustained.We calculated reach by observing and counting the number of visitors to either the farmers' market or the revitalized retail district and dividing this value by the number of people residing in the predesignated geographic area. We calculated effectiveness as the proportion of visitors engaged in the desired health behavior (i.e., purchasing fruit and vegetables or actively commuting to the retail district).Adoption was calculated as the percentage of invited agencies and individuals participating in the planning and approval process (including those involved in implementing and maintaining the change). We rated implementation using an anchored scale based on the extent to which implementation deviated from preestablished criteria (e.g., for the farmers' market, adherence to the planned number of vendors and the diversity and cost of food and, for the complete streets example, adherence to established design guidelines).Finally, we estimated maintenance using a similarly constructed anchored scale based on the likelihood that the environmental change (and resulting reach and effectiveness) would be sustained (and measured subsequently via periodic observations). The summary scores for the 2 projects were close (0.47 and 0.53) despite wide variation on the separate dimensions.

This suggests that important information, such as whether a sustainability plan has been discussed, may be obscured if summary scores alone are used. Second ApproachA second approach is to form a composite score by multiplying the 0.0 to 1.0 reach score by the 0.0 to 1.0 effectiveness score (R × E). The scores for the 2 examples (0.06 and 0.014) mask large differences in effectiveness (0.60 and 0.05; ). Although the R × E score is relatively simple to calculate (because it eliminates the less straightforward adoption, implementation, and maintenance ratings), it removes those aspects of RE-AIM that are most likely to affect reach and sustainability (i.e., the participation of adopters with the authority to approve the project and the likelihood that it will be maintained).

Third ApproachA third and related index recommended by Glasgow is the “efficiency index,” in which the cost of the built intervention is divided by the R × E metric. Including cost information may appeal to decision makers and investors tasked with allocating scarce resources. However, estimating true costs may not be practical for large, multifaceted infrastructure changes, particularly given that large capital investments may be offset by civic and social benefits (e.g., increased commerce and jobs, traffic and crime safety), in addition to improved health behaviors. One way to address such situations would be to parse out the costs most directly related to the targeted health behavior, such as the costs of walking and biking infrastructure improvements.In general, the efficiency index method may be best suited to projects (e.g., community gardens, trails, or playgrounds) in which the direct costs of implementation and maintenance are closely related to the R × E score. The issue of who collects, analyzes, and summarizes these data for decision makers is a complex one whose detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this article.

We recommend that a neutral party, such as a state health representative or an independent evaluation firm, conduct these analyses.Presenting RE-AIM data in a way that resonates with the general public is another complex issue. Use of graphic representations, such as charts that illustrate the relative strength of each dimension, may better facilitate communication and decision making than use of numerical scores. DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONSThe 5 RE-AIM dimensions, with some modification of definitions, seem to be applicable to built environment interventions and provide added value given their usefulness in anticipating impact, planning for sustainability, and addressing unexpected or adverse consequences.

The greatest modification with respect to both planning and evaluation was associated with the adoption dimension. Because built environment interventions do not involve acceptance by a specified set of institutions or organizations such as schools or worksites, identifying the participation and characteristics of adopters is less central than is identifying and including those with the authority to approve the project and those involved in its implementation, enforcement, or maintenance. Although the specific adopters may change as the project moves from planning and design to implementation, anticipating and including all critical stakeholders and end users during the planning stage will reduce the likelihood of costly delays, revisions, or cancellations.An advantage of using RE-AIM is that it ties together key concepts that can be used in both planning and evaluating built environment projects. The model can be applied to various scenarios to compare and make decisions regarding how a proposed project's location affects reach, which agencies and organizations need to be brought to the table, and the relative costs of different project scenarios. A disadvantage of using RE-AIM is its conceptual nature; that is, the framework does not provide guidelines on what specific data to collect, how to collect these data, or how to monitor “exposure” to the project and its impact on behaviors over time. Thus, community groups may find it challenging to address all 5 dimensions of RE-AIM in a practical manner.On a related note, measurement recommendations for built environment interventions may demand expertise that is beyond the means of many community organizations. Recruiting individuals and measuring their health and health behaviors longitudinally is often not an option.

However, changes in behavior can be adequately captured by community volunteers trained in using qualitative techniques such as systematic observation and behavior mapping.In addition, if diverse partners are involved in the design and implementation phases, data already collected for other purposes (e.g., sales receipts, crime and accident statistics) can also be used to quantify reach and effectiveness. Even if it is not possible to measure all aspects of the RE-AIM framework for a given built environment intervention, consideration of all dimensions in the planning stage, including qualitative assessments of relevant metrics (e.g., the characteristics of who is, and who is not, participating and benefiting ), can enhance the success of the intervention.A follow-up question that emerges from this application of RE-AIM is whether a particular RE-AIM dimension should be weighted more heavily than others or whether a summary score can suffice. The answer to this question depends on the situation.

As our examples showed, comparing an average summary score across RE-AIM dimensions may obscure important elements such as inclusion of key stakeholders or plans for maintaining the change. Also, a summary score is not meaningful in and of itself because it has no referents or norms.

Evaluation And Maintenance Of Mis Ppt

Implementation Evaluation And Maintenance Of The Mis Pdf Format

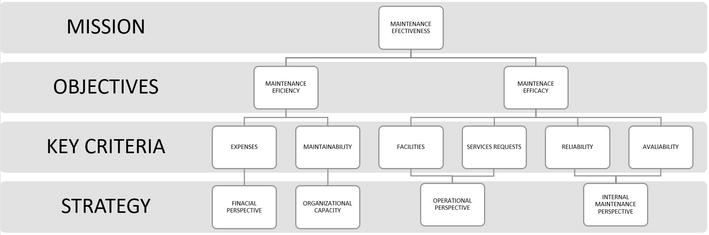

During the growth of a competitive global environment, there is considerable pressure on most organisations to make their operational, tactical, and strategic process more efficient and effective.An information system (IS) is a group of components which can increase the competitiveness and gain better information for decision making. Consequently, many organisations decide to implement IS in order to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of their organisationsInformation systems have become a major function area of business administration. The systems, nowadays, plays a vital role in the e-business and e-commerce operations, enterprise collaboration and management, and strategic success of the business.